Memory Mapping

| On path: Memory | 1: Memory • 2: Memory Management • 3: Memory Sizes • 4: Memory Mapping • 5: Memory Segmentation • 6: Memory Protection • 7: Virtual Memory • 8: Paging • 9: Memory Management Unit (MMU) • 10: Caching • 11: Cache • 12: Translation Look-aside Buffer (TLB) |

|---|

| Depends on | Memory Management |

|---|

The purposes of this page are:

- to introduce the concept of virtual and physical addresses

- to look at the process of address translation

- Computer memory is a physical storage medium; it holds one data item per location (address).

- A running process uses an address to specify a location to load (read) data from or store (write) data to memory.

- Each process has its own, independent set of addresses it wants to use.

- In a multiprocessing system it is important that processes do not interfere with each other.

It is possible to resolve this issue by compiling and selecting the processes very carefully – but this is not a particularly convenient solution. A common approach is to use virtual memory.

Each process can attempt to use any virtual address and there can be many overlaps in values. However, a virtual address is pointless by itself - it needs to point to some data, most likely in some physical location, in order to be useful to a program!

In a virtual memory system, a process’ address is referred to as a “virtual address”; this is translated to a physical address such that each physical location has a single correspondence with a process-plus-virtual-address combination.

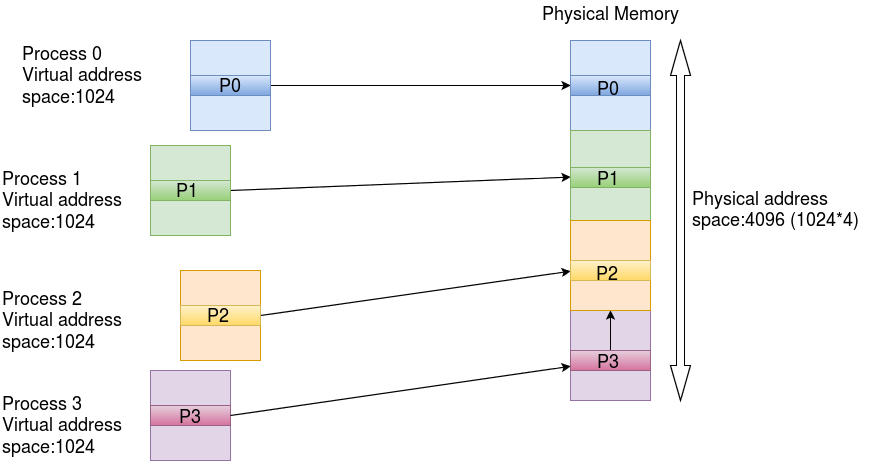

A simple way to do this would be to have (say) four times as much physical memory than the virtual address could reach, then concatenate the process number {0,1,2,3} and the virtual address.

This is a poor solution though, in that it requires a lot of memory (expensive!) and yet supports a limited number (four, here) of processes.

So, usually, this is not a practical approach.

Observations:

- Very few processes use the whole of their virtual address space.

- It may be hard to predict which virtual addresses a given process chooses to use.

- There is typically significant locality of access: if one address is used it is likely that addresses around it are also used.

Examples: instructions in a program; stack data; objects …

These properties are therefore exploited when memory mapping virtual to physical addresses, a process usually called “address translation”.

(Note: it is important to understand the next bit, so take your time.)

Address translation

Here is an illustration of address translation, in a miniature, (8-bit) form.

Points to note:

- Addresses are translated from a virtual address space (the addresses the application is aware of) to a physical address which the memory hardware deals with. The O.S. is involved because it sets up the translations.

- Addresses are not translated individually: they are organised into pages which share a translation.

This keeps the size of the tables manageable.- In this example, each page contains 32 (25) bytes: real pages are a bit larger than this.

- In this example, there are only 8 (23) pages: real systems will have a few more.

- Addresses are not translated individually: they are organised into pages which share a translation.

- The most significant bits of the address are used to define the page number. Only the page number is translated.

- Translations are an arbitrary look-up process in a page table.

- It is possible to alias more than one virtual page to the same physical page (try it) – although this is not usually useful in practice.

- Not all virtual pages need an allocation of physical RAM.

A page can be marked as ‘invalid’ if it is not wanted.

In a real system (larger virtual space) most pages are not wanted.

- The page table may have some ‘spare’ bits which can be used for other purposes.

In the example below, there is an 8-bit entry with 1 bit used for validity and another 3 bits used for the physical page number. Other bits are suggested by ‘?’ here. Some of these bits can be used for purposes such as memory protection.

Interactive demonstration

Virtual Address in hex

Virtual Address in binary

Virtual Address index (3 bits)

Virtual Address offset (5 bits)

Physical Address

Exercise: play with this mechanism until you understand the principle.

Click a page table entry to change the valid bit and set the page frame number.

Click a page table entry to change the valid bit and set the page frame number.

Practically, the mapping is done in hardware by a Memory Management Unit (MMU) which usually has its page tables stored in RAM. (Here the (single) page table has been drawn separately, for clarity.)

Larger address spaces

Real memory mapping has to deal with 32- or 64-bit addresses and is a bit more complicated, but the principle is still the same. The problem comes from the potential size of the tables as each process needs a page table with as many entries as there could be pages.

Illustration A ‘small’ utility (e.g. a version of

ls) might be about 111 KiB (one version looked at was). In a 32-bit system with 4 KiB pages this would use about (depending on its exact address alignment) 28 pages; a single-level page table would require 220 entries for this process. As each entry is probably 32 bits long, this requires 4 MiB to support the 100+KiB process. This is poor utilisation. In an equivalent 64-bit system 252 64 bit entries: that’s 32 PiB or “a #*|! of a lot” of memory to support each process. Totally infeasible in a single array.

This is problem is addressed (excuse the pun!) by using hierarchical page tables.

See also memory sizes.

| Also refer to: | Operating System Concepts, 10th Edition: Chapter 10.1, pages 389-392 |

|---|