Memory Management Unit (MMU)

| On path: Memory | 1: Memory • 2: Memory Management • 3: Memory Sizes • 4: Memory Mapping • 5: Memory Segmentation • 6: Memory Protection • 7: Virtual Memory • 8: Paging • 9: Memory Management Unit (MMU) • 10: Caching • 11: Cache • 12: Translation Look-aside Buffer (TLB) |

|---|

| Depends on | Memory Mapping • Virtual Memory • Memory Protection • Context |

|---|

It would be a good strategy to be familiar at the simplified principles of memory mapping and memory protection before getting too deeply into this article, as the MMU is where they meet.

Caveat: different MMUs will be implemented in ways which differ in detail. This page is intended to illustrate the general principles in a particular way.

MMU Definition

A Memory Management Unit (MMU) is the hardware system which performs both virtual memory mapping and checks the current privilege to keep user processes separated from the operating system — and each other. In addition it helps to prevent caching of ‘volatile’ memory regions (such as areas containing I/O peripherals.

MMU inputs

- a virtual memory address

- an operation: read/write, maybe a transfer size

- the processor’s privilege information

MMU outputs

- a physical memory address

- cachability (etc.) information

or

- a rejection (memory fault) indicating:

- no physical memory (currently) mapped to the requested page

- illegal operation (e.g. writing to a ‘read only’ area)

- privilege violation (e.g. user tries to get at O.S. space)

Example

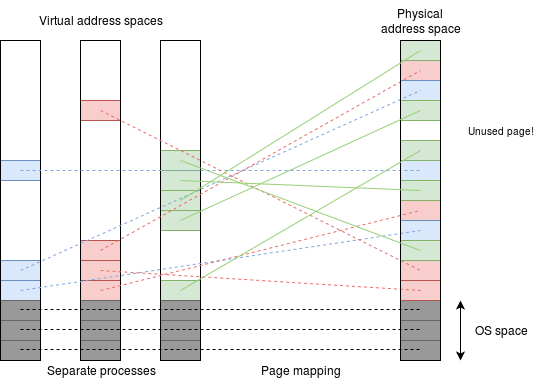

A typical MMU in a virtual memory system will use a paging system. The page tables specify the translation from the virtual to the physical page addresses; only one set of page tables will be present at any time (green, in the figure below) although other pages may still be present until the physical memory is ‘overflowing’, after which they may need to be “paged out”.

All the current process’ pages must be in the page tables but they need not all be physically present: they may have been ‘backed off’ onto disk. In this case the MMU notes the fact and the O.S. will have to fetch them on demand.

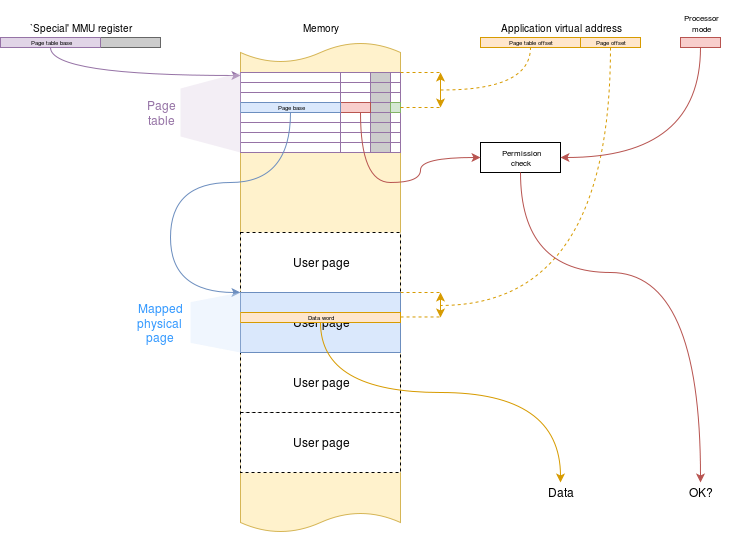

As was observed in the memory mapping article, the page table entries have some ‘spare’ space. Part of this indicates things like “this page is writeable” and the MMU checks each access request against this. Only if there is a valid mapping and the operation is legitimate will the MMU let the processor continue, otherwise it will indicate a memory fault.

Architecture

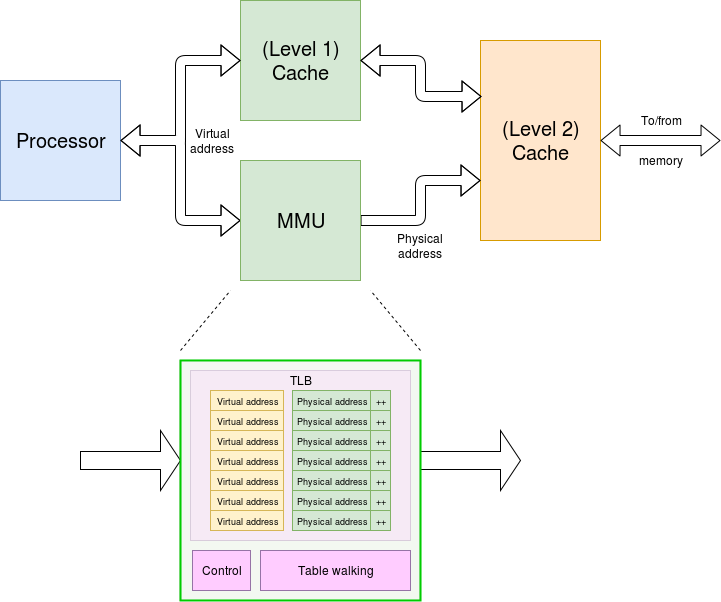

The figure below shows a typical MMU ‘in situ’ This translates virtual to physical addresses, usually fairly quickly using a look-up (TLB). This also returns some extra information – copied from the page tables – such as access permissions. If the virtual address is found in the (virtually addressed) level 1 cache then the address translation is discarded as it is not needed; the permission check is still performed though because (for example) the particular access could be a user application hitting some cached operating system (privileged) data.

The look-up takes some time, so it is usually done in parallel (“lookaside”) with the first level cache, which is why the level 1 cache is keyed with virtual addresses – something which is of importance during context switching.

Example page table structure

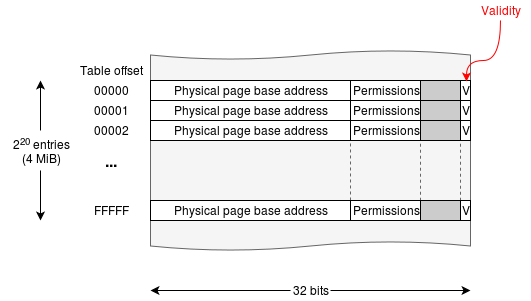

The figure below shows a simple page table for a 32-bit machine using 4 KiB pages (212 bytes), leaving 20 bits to select the page (220 = 1048576 pages).

Implementation

Because page tables are quite large – and there must be a set for each process – they, themselves need to be stored in memory. This means that they are accessible for the O.S. software to maintain them – they must be in O.S. space for security, of course – but makes the memory access process very slow (and energy inefficient, too) because (in principle) there is one (or more) O.S. look-ups before every user data transfer takes place. If this really had to happen the computer would be horrendously inefficient!

In the ‘definition’, above, the MMU function was defined as a ‘black box’; a common set of page translations can be cached locally to avoid the extra accesses, most of the time. This is the function of the TLB.

In practice the TLB will satisfy most memory requests without needing to check the ‘official’ page tables. Occasionally, the TLB misses: this then causes the MMU to stall the processor whilst it looks up the reference and (usually) updates the TLB contents. This process is known as “table walking”; it is usually a hardware job so you don’t have to worry about the details in this course unit.

| Also refer to: | Operating System Concepts, 10th Edition: Chapter 9.1.3, pages 353-355 |

|---|