Virtual Memory

| On path: Memory | 1: Memory • 2: Memory Management • 3: Memory Sizes • 4: Memory Mapping • 5: Memory Segmentation • 6: Memory Protection • 7: Virtual Memory • 8: Paging • 9: Memory Management Unit (MMU) • 10: Caching • 11: Cache • 12: Translation Look-aside Buffer (TLB) |

|---|

| Depends on | Memory Mapping • Memory Protection • Virtualisation • Concepts |

|---|

This is an overview: you may need to explore some constituent parts before it becomes completely clear.

One of the most important functions of an operating system is to provide an abstracted virtual environment for applications code. An application has an idealised view of the machine (any machine) it is running on. A major consideration is the address space of the system.

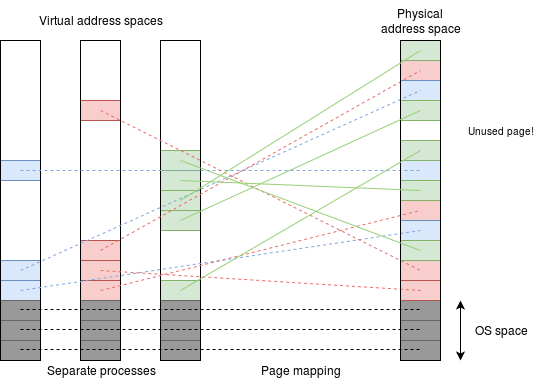

Different machines may have different amounts of physical memory installed: it depends on what you pay for. However, in a virtual memory system the application can simply assume that ’all’ the memory – the amount being set by the virtual machine size – is present and it can use any which it wants. This is also independent of other applications which may be running concurrently – which can also use any address they want, including those which conflict.

To achieve this, each process has a private map which translates the virtual addresses (the ones the application generates) into non-conflicting physical addresses. This solves any potential address address conflicts. Any application only knows its own virtual addresses; the physical addresses are only known only within the O.S.

Benefits

It must first be noted that the amount of memory available has followed ’Moore’s Law’ and that the (virtual) address space of popular processors has had to mirror that. For general convenience (and, somewhat, by convention) although memory sizes double or quadruple in each process generation, architectures have doubled the number of bits, thus progressed in fewer, bigger steps.

The first really widespread microprocessors were “8-bit” (which, typically used 16-bit addresses); the next generation were “16-bit” (address sizes being expanded by various stratagems to 20- or 24-bits); thence to “32-bit” machines (addresses are/were often also 32-bits) and currently to “64-bit” processors (addresses may be reduced to (say) 56 bits).

- Early in a processor generation it is infeasible to fill the available address space with physical memory (even for a single process). Virtual memory allows the physical memory to appear in the places it is wanted.

- Late in a processor generation there may be more physical memory than fits in the address space. Virtual memory allows the physical memory to be used sensibly to support multiple processes without needing to ’swap’ (see below).

Observations

- Very few processes use the whole of their virtual address space.

- It may be hard to predict which virtual addresses a given process chooses to use.

- There is, typically, significant locality of access: if one address is used it is likely that addresses around it are also used.

Examples: instructions in a program; stack data; objects … These properties are therefore exploited when memory mapping virtual to physical addresses, a process usually called “address translation”.

Swapping

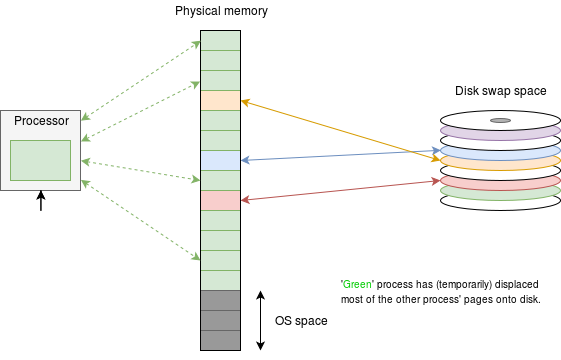

Mapping the memory works okay providing that the sum of the memory used by all current applications does not exceed the size of the installed physical memory. If that happens then some more storage needs to be found: the solution is to use some secondary storage which is likely to be a magnetic disk.

If the demand on the physical store becomes too great, some pages are copied onto disk to free up some new space. The pages are chosen by (inspired) guesswork as to which will probably not be needed in the near future by a scheduling algorithm; this is the same principle as caching. The process is usually referred to as “paging” or “swapping”.

Swapping keeps everything running but each swap is time-consuming, so as swapping increases the applications (i.e. “the computer”) will slow down. You will probably have witnessed this. Buying more (electronic) memory (RAM) will delay the point where extensive swapping becomes necessary – hence a ’faster’ machine if you want to run lots of applications or memory-hungry applications.

Sounds familiar?

How is it done?

Answer: with a combination of hardware and (operating system) software.

This is explained across various articles; the key concepts are probably:

- Memory mapping keeps the application code supplied with memory.

- Memory protection keeps the applications secure and separated.

- The MMU is the hardware which implements all this.

- Paging supports swapping to disk.

Video (12 mins.) on virtual (or, possibly, “virutal”!) memory.

Memory sizes

The extent of the virtual address space is set by the hardware architecture of the machine: a “64-bit” machine can address 264 bytes. This is what the programmer sees.

The extent of the physical address space is fixed in hardware and is often (but does not have to be) the same size as the virtual address space.

Contemporary x86-64 system ’only’ support a 48-bit physical address (256 TiB), for example.

The amount of physical RAM is anything up to the supported address space, subject to limitations of cost, power/cooling and room in the machine.

| Also refer to: | Operating System Concepts, 10th Edition: Chapter 10, pages 389-440 |

|---|